The Story of the American Expeditionary Forces |

III Corps |

Little Louis and Big Bertha

By

Mark G McLaughlin

|

"This is some gun," Louis wrote on the back of the photo, which he sent home to his wife, Lillian. in November 1918. "It shoots nearly 35 miles and when it lands it puts a hole in the ground as big as 4 houses. The bullet weighs 500 pounds. I do remember it well. It is 60 feet long. It is built all in one with 24 wheels on it."

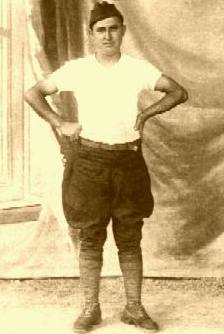

O Pioneers!The United States Army formed many pioneer infantry regiments for World War One. They were cross-trained in combat engineering and infantry tactics. As one of their officers remarked "they did everything the Infantry was too proud to do, and the Engineers too lazy to do."The pioneer regiments included such specialists as mechanics, carpenters, farriers and masons. They were supposed to work under the direction of the Engineers to build roads, bridges, gun emplacements and camps "within the sound of the guns." They received standard infantry training so that they could defend themselves, but there are very few documented instances of any pioneer troops unslinging their rifles. Unfortunately, Louis Raab was involved in one of those few such incidents. That came during the "Big Show," as General John "Black Jack" Pershing called the Meuse-Argonne offensive he launched in late September, 1918. Little Louis Joins The ArmyLouis Raab was a 27 year-old licensed plumber and married man when America entered World War I. His father and mother had come to America from Bavaria to escape the Kaiser and his German Empire in 1866. Louis and his eight siblings were born in Albany, New York, where their parents built the city's first "Bier Garten." (The Garden Grill still stands on 2nd Avenue. Louis's youngest brother, Freddy, tended bar there until 1985). Eager to prove that he and his German-speaking family were "real Americans," Louis volunteered to join the army. He signed up with the battle-hardened 14th New York National Guard. (The 14th fought in Mexico from August through October 1916, and was recalled to federal service on July 20, 1917.) Most of its companies were drafted into the 2nd Pioneers.A certified tradesman, Louis was just the sort of man the army wanted in its Pioneer units. In its infinite wisdom, the army decided that although Louis had been a plumber since his early teen years, he would make a good cook. After all, the staff sergeant told Louis "your family owns a restaurant, so you must be able to cook." Louis tried to explain that the only thing that the Bier Garten served was beer (and an occasional knockwurst), but the sergeant did not care; he declared Louis to be a cook.  Louis [on left] At a Cook ShackMad Plumbers Make Bad CooksThere are many photographs from Camp Bassens showing my grandfather at his mess tent, in his cook's hat and apron. He remembered cooking a lot of rice and of making such uniquely army dishes as "Goldfish Loaf" (a baked concoction of canned salmon and bread crumbs), "Corn Willy Hash" (canned corned beef with potatoes) and his favorite, "Fried Mush" (sliced cornbread fried and drowned in sweet syrup). Unfortunately, my grandfather also baked a cake one day for the captain's birthday. My grandfather and his buddies did not like the captain, and they convinced Louis to use laxatives when baking the cake. The captain got the "two-step trots" and Louis was cashiered from the cook tent. That is when Louis became a real Pioneer.Under FireThe 1st and 2nd Pioneers were attached to support General Hunter Liggett's First Army Corps and Major General Bullard's Third Army Corps, both of which were to participate in the joint Allied offensive to crack the Marne salient. The Pioneers' job was to build roads through the thickly forested terrain. From the beginning of the campaign the pioneers were under constant and often heavy fire from German artillery. (Including, as my grandfather swore, the huge railway gun known as "Big Bertha.") The road construction gangs were bombed and strafed by German planes (the Allies did not always have air superiority). As the infantry advanced, the pioneers kept pace. They built roads, salvaged ammunition from burnt-out trucks and abandoned artillery positions and helped bring supplies forward. The pioneers were so close to the fighting that they were often under heavy machine-gun fire.When the Aisne-Marne offensive petered out near the end of August, the Pioneers were shifted down the line to the Meuse-Argonne front. From late September until Armistice Day (November 11) they built the roads that allowed the army to advance through the tangled Argonne Forest. Under direction of engineer officers, Louis and his fellows bridged the Aisne, Aire and mighty Meuse Rivers -- and did it under fire.  Work on Meuse Bridge by US Engineers or PioneersAn Extra Year In FranceThe Armistice did not bring an end to duty in France for Louis or the rest of the 2nd Pioneers. They were among the troops selected to stay behind, along with the labor battalions, to help "clean up" the war zone. They did everything from clear mine fields and salvage equipment to build and guard prisoner of war camps. Louis, who spoke fluent German, was tasked for the later duty. He made many friends among the German soldiers, several of whom made rings and other pieces of jewelry to trade for extra rations.In November 1919, a year after the fighting had come to an end, Louis and the 2nd Pioneers were sent home. They were mustered out at Camp Dix, New Jersey.  My Grandfather |

Before Mess Tent |

"A soldier dreams of the Golden West,

where sunshine beams from crest to crest,

where men and women strive for the right

and struggle for justice against the curse of might."

By October, 1918, Louis was a veteran who had been under nearly constant fire. In a card from that month he wrote home this lament:

Souvenir of France

Louis's mood rebounded, of course, with the signing of the Armistice. In a postcard sent home from Bordeaux (where he went to have a minor wound treated) he wrote:

"Hurrah for the victory!

Under the glorious flag

our battle was won!"

Acknowledgements and Sources:

Special thanks to the following who provided information on the 2nd Pioneers:- Louise Arnold-Friend, Reference Librarian, US Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

- Mike Hanlon, editor of the Doughboy Center (www.worldwar1.com/dbc).

- Thisted, Mose N. Pershing's Pioneer Infantry of World War I. Alphabet Printers, Hemet, California, 1982.

- Barbeau, Arthur E. and Henri, Florette. The Unknown Soldiers: Black American Troops in World War I. Temple University Press, 1974.

To find other Doughboy Features visit our |

Membership Information  Click on Icon |

For further information on the events of 1914-1918

visit the homepage of |

Michael E. Hanlon (medwardh@hotmail.com) regarding content,

or toMike Iavarone (mikei01@execpc.com) regarding form and function.

Original artwork & copy; © 1998-2002, The Great War Society