A Survey of New York City World War I Monuments

Contributed by

Laura Canon (lauracanon@yahoo.com)

|

New York had closer ties to the war than much of the rest of the country. The terrific amount of maritime traffic alone employed thousands of New Yorkers and exposed to danger non-combatants like the men of the Merchant Marine. Meanwhile, hometown regiments like the "Fighting 69th" and the "Harlem Hellfighters" were in the thick of the fighting. For this reason, the city has quite a number of World War I memorials. The motives behind them range every aspect of feeling about the war - patriotism, sorrow, idealism. They are found today at obscure street crossings in Brooklyn and Queens and high up on the sides of public buildings in downtown Manhattan. Some are hidden and forgotten; some have become part of their community.

The first World War One memorial in the United States was the clock in the tower of Pier A, Battery Park, lower Manhattan, dedicated in 1919. At that time the pier was heavily used for passenger shipping but gradual changes and a decline in port traffic have led to the pier being closed to the public, which means it can only be viewed from a distance. As far as I can tell, there is no sign on the clock, but the original facade has been replaced by metal sheeting. The Pier is currently surrounded by scaffolding and is undergoing restoration.

Most of the memorials in New York City were not actually put up by the city, but by the local regimental armories. The Gold Star Mothers (a group of mothers whose sons had been killed in the war) donated this statue of a doughboy which stands in front of the armory of the 14th New York regiment in Park Slope, Brooklyn. The regiment stopped using the armory in the 1960s and for several years it was in disrepair. At one point the Army, fearing vandalism, decided to remove the monument. A protest, led by the community and a veteran's group, saved it. The building and grounds have now been spruced up and look rather nice. On Memorial Day and Veteran's Day wreathes are laid by the veteran's group.

The typical World War I monument of the city's streets is bronze and heroic, preferably with a bayonet flourish, like this one in a grungy little plaza in front of the Health Department in Chelsea, lower Manhattan. Note that the dates on it cover the period before the US entered the war. Since it is dedicated to the "Soldiers and Sailors" of the neighborhood (Chelsea has a long maritime history) this may be to cover those who died from German ship sinkings in the period of neutrality.

Similar to the Chelsea statue is the 7th Regiment memorial on Central Park and East 67th Street, a block away from their armory. This was not the place for questions. Glory in bronze and the fixed bayonet…!

Brooklyn's official war memorial (the Bronx also has one, and Queens) was erected in 1921 in Prospect Park. Unlike the armory statues it is somber and somewhat mysterious. Behind the angelic figure supporting (or gathering in?) a weary soldier in puttees are the names of the borough's war dead on long panels, some of which are now missing. Consciously or unconsciously it reflects a post-war mood of loss and sadness, as well as the death of ideals. (An inscription below says that they died for "the cause of universal peace.") An interesting feature is that it is dedicated to the "men and women" who died in the conflict. Searching the lists of names I could find only one female one - that of Daisy M. Kirkterp, an RCN.

Like the Prospect Park statue, this one on the edge of Forest Park in Queens is somber and rather reflective. It was put up neither by an armory or the city but by the community of Richmond Hill, which wished to commemorate the contributions of its men. It speaks of war fought not with bayonets but with determination and noble self-sacrifice, an attitude very different from the armory statues and very much of its era.

On perhaps hundreds of walls throughout the city are smaller, no less sincere testaments to men and times now gone. This one across the front of P.S. 134, on 18th Avenue in Brooklyn, is a window on its time with its mostly English and Irish names (this part of Brooklyn was then a wealthy, rather sparsely populated suburb), quote from the Gettysburg address, and restrained design. The plaque was refurbished a few years ago by the Board of Ed and the stars indicating those students who were killed (there were three or four, as I recall) somehow vanished in the process!

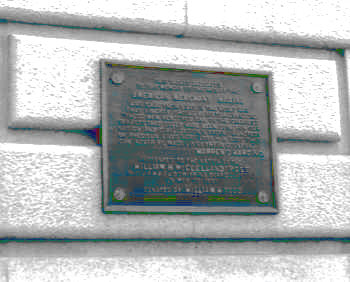

Slightly more fulsome is this plaque dedicated to the men of the Merchant Marine and adorned with a longer quote from President Warren G. Harding - not a noted orator. "These men rendered one of the greatest services that could have been done for our nation and civilization's cause. Hundreds of precious lives were lost - a loss that can never be made up by their country." In 1921 the building to which this plaque was attached was the Customs House, through which all ship passengers had to pass. The same forces that led to the closure of Pier A in Battery Park ended that, and today the building is the National Museum of the American Indian.

This plaque, on the other hand, near 95th Street in Central Park, is certainly noticeable and must mystify the joggers who pass on their daily rounds. Who was John Purroy Mitchel and why did he get such an elaborate personal monument? Mitchel was elected Mayor of New York City in 1913 at the age of 25. Nicknamed "the Boy Mayor" he was the youngest person ever to hold that office. After losing the election of 1917 he volunteered, like so many other young men, for the Army Air Corps. While in training in 1918 he was killed in a strange accident, apparently falling out of his plane.

In the early 1920s, while city officials quarreled over what kind of official monuments should be erected, planting trees to the memories of individual New York City soldiers became popular. In Central Park, Madison Square Park and Harlem's Jefferson Park oak trees were planted, and in Brooklyn along Bedford Avenue 2,300 elm sapling were dedicated. Today memorial trees can still be found beside the Brooklyn Public Library on Grand Army Plaza and along Prospect Park West. (Possibly these are the same trees planted on Bedford Avenue, which were later moved by subway construction.) Each tree has a small plaque in the cobblestones around its roots with the name of a soldier (most are privates or corporals) and his regiment.

Another official method of recognition was street names. (John Purroy Mitchel, for instance, also got Mitchell Place in Manhattan named after him.) In 1928 Avenue A was transformed into York Avenue after Sergeant York. But certainly the most celebrated of the city's regiments was the "Fighting 69th," a mainly Irish regiment from Manhattan. As anyone who has seen the film can testify, the major figures of legend were Father Duffy, a chaplain whose statue now adorns Times Square, and brave young Sergeant Joyce Kilmer, America's Rupert Brooke, whose death inspires James Cagney to kill 15 Germans with his bare hands (or something like that.) Kilmer, actually a native of New Jersey, became a very popular figure and two New York City boroughs named street features after him. The Bronx's Joyce Kilmer Park sits alongside the courthouse, while Brooklyn's Joyce Kilmer Square is a sliver of a shopping district along Kings Highway. Other streets named after soldiers include Finn Square in Tribeca, lower Manhattan, (no longer marked), named after the son of a Tammany Hall leader who fell in the "Fighting 69th," and Henshaw and Staff streets in upper Manhattan. Regimental armories also serve as memorials - the 69th Armory, on Lexington Avenue and 26th Street, is typical in its fortress-like architecture. The 369th ("Harlem Hellfighters") armory, at Fifth Avenue and 142nd Street, is more modern. Erected in 1923, the interior contains memorials to the soldiers of the war which brought the regiment its lasting fame.

I'm sure there are some memorials I have not yet discovered.

Though some were in guidebooks, I found most of them simply through

passing them by on my way to somewhere else. Since I have lived

in Manhattan and Brooklyn I tend to know more places there than

in the other boroughs. If anyone is interested in adding to this

list please e-mail me: lcanon@msn.com. © 1997-1999 Laura Canon - All rights reserved |

<

<