May |

Access |

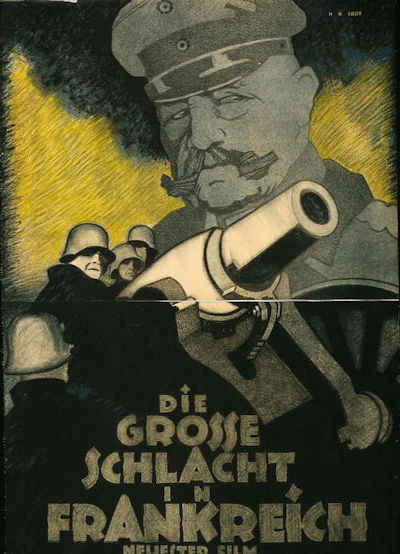

Hindenburg and Ludendorff

|

Poster for WWI Propaganda

|

|||||

Free Publications |

||

|

Amazon.com |

||

Who Succeeded Hindenburg & Ludendorff on the Eastern Front

Prince Leopold

In August 1916, when Paul von Hindenburg was named Germany's Chief of the Great General Staff, his command position for the Eastern Front, Oberbefehlshaber Ost, was assigned to 70-year-old Prince Leopold of Bavaria. As an Army and Army Group commander, he had been responsible for the capture of Warsaw and helping reverse the early successes of the Brusilov Offensive. With the aid of his brilliant Chief of Staff Max Hoffman, he would bring the campaign in the East to a victorious conclusion.

The Stakes at Tannenberg

The Tannenberg Victory Memorial

Site of Hindenburg's Funeral (Later Destroyed)

We had not merely to win a victory over Samsonov. We had to annihilate him.

Only thus could we get a free hand to deal with the second enemy, Rennenkampf,

who was even then plundering and burning East Prussia. Only thus could we

really and completely free our old Prussian land and be in a position to do

something else which was expected of us – intervene in the mighty battle for a

decision that was raging between Russia and our Austro-Hungarian ally in Galicia

and Poland. If this first blow was not final the danger for our homeland would

become like a lingering disease, the burnings and murders in East Prussia would

remain unavenged, and our Allies in the south would wait for us in vain. . .

from Out of My Life

[As] the crisis of the battle now approached. One question forced itself upon

us. How would the situation develop if these mighty movements and the enemy’s

superiority in numbers delayed the decision for days? Is it surprising that misgivings

filled many a heart, that firm resolution began to yield to vacillation, and that

doubts crept in where a clear vision had hitherto prevailed? Would it not be wiser

to strengthen our line facing Rennenkampf again and be content with half-measures against Samsonov? Was it not better to abandon the idea of destroying

the Narew [Second] Army in order to ensure ourselves against destruction.

Paul von Hindenburg, 1920

Hindenburg–Ludendorff:

Tannenberg and the Cult of Hindenburg

Ludendorff and the Man Most Responsible for

the Tannenberg Victory, Max Hoffman

the Tannenberg Victory, Max Hoffman

Tannenberg (26-30 August 1914), the best-known battle of the Eastern Front, was primarily planned by the staff of the German Eighth Army as their commander was being replaced. Able to track the advancing Russian Second Army because of their poor signal security, the Germans spotted their opportunity to thoroughly defeat it. Their new leadership decided to transfer German forces southward via rail. There they found the Russian forces widely dispersed and were able to defeat the corps guarding each flank and drive back their center. Ignoring orders, I Corps commander General von François cut the enemy's line of retreat. About half of the Second Army was surrounded and eventually surrendered. Their commander General Samsonov went into the forest and shot himself.

Nine days later, the duo moved north and delivered a second dramatic victory for Germany at Masurian Lakes (9-14 September 1914). After the victory at Tannenberg, Ludendorff decided to focus again on the Russian First Army back to the north.

Reinforced by two corps from the western theater, Eighth Army attacked with the intent of driving the Russian forces, which had moved to a more defensible position after the annihilation of Second Army, to the coast. A successful attack by General François's I Corps against the southern First Army flank compelled a retreat. A complete route was prevented by a two-division Russian counterattack in the center that allowed a withdrawal to proceed. It was the second massive defeat for the Russian Army

and led to the dismissal of Army Group commander Zhilinsky. With the two victories, Hindenburg-Ludendorff had eliminated any direct threat to the German homeland. On 1 November 1914 Hindenburg was appointed Ober Ost (commander in the east) and was promoted to field marshal.

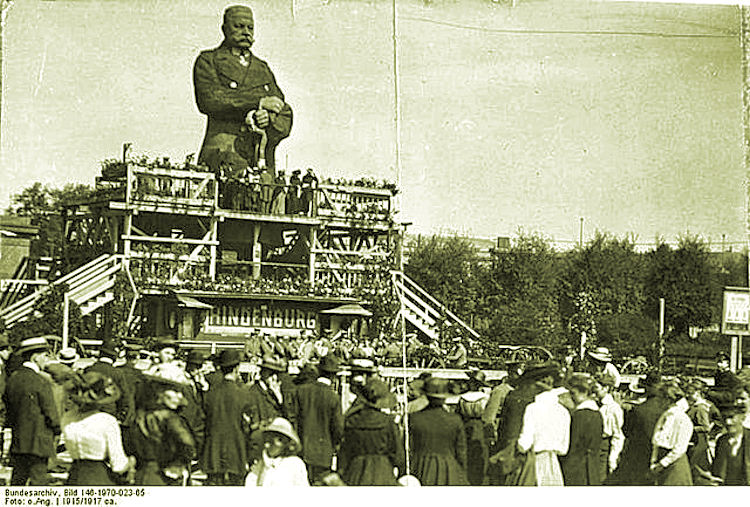

1915: A Stupendous Tribute to Hindenburg

Unveiled in Berlin

Despite their minimal conceptual contribution to the victory at Tannenberg, the new partnership received full credit from the Kaiser and the Army for the successes. Being the face of the leadership, Hindenburg received all the public glory and honors as the savior of East Prussia. The news of the victories in the east—for the time being—counteracted the implications of the defeat at the Marne, that the promising start in the west had been halted and that a long war was now a certainty.

Within weeks of Tannenberg, the German population exalted Hindenburg to mythical heights. He became a symbol of victory and unity at home—a role traditionally reserved for the Kaiser. The new national hero was showered with official honors, and the country was flooded with Hindenburg souvenirs. Known for his sangfroid, Hindenburg seemed to personify Germany’s superior mental strength, a key theme of German war propaganda. His rectangular features and broad frame projected a specific type of masculinity and virile gravitas. He was often depicted as a rock in the ocean that kept back the tidal waves of the enemy’s onslaught. Hindenburg turned into Germany’s supreme symbolic figure and soon eclipsed Emperor Wilhelm II' public standing, raising concerns that his popular appeal had introduced a plebiscitary element into German politics that threatened the monarchy. The field marshal was not shy about using his symbolic capital for political gain. From 1915 onward, Hindenburg, supreme commander of German troops on the Eastern Front since November 1914, repeatedly threatened the Kaiser with his resignation in order to push through his own agenda. By 1916, when the war started taking a bad turn for Germany, the partnership would be well placed for further advancement.

Sources: Encyclopedia 1914-1918 Online; Over the Top, December 2014

Hindenburg–Ludendorff:

Gaining Supreme Command

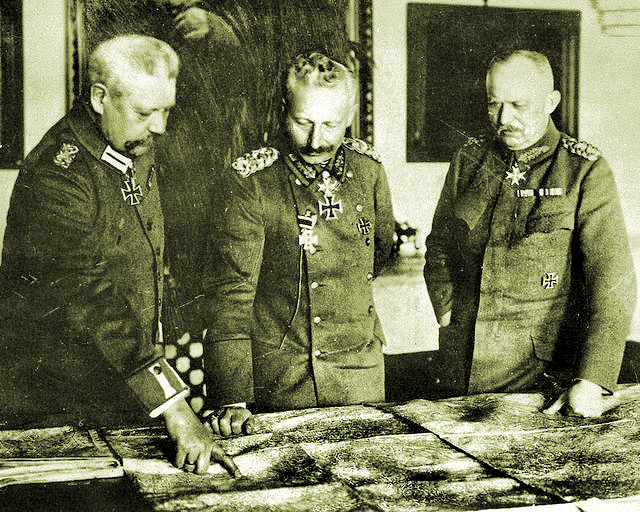

Ober Ost Command & Staff in the Field

The duo would spend the next 22 months of their collaboration in the east attempting to knock Russia out of the war. They would be constrained and sometimes fully frustrated by two factors. In the words of Eastern Front historian Norman Stone the pattern of the war in the east was of "more or less constant Austro-Hungarian crisis." After their early successes in the Fall of 1914, the partnership—mindful of the early failed Austrian offensive in the south—got their first taste of cries for help from their weaker ally when they were compelled to send a German division to help hold the Russians out of Hungary in December of 1914. Much has been written about how burdensome the Austro-Hungarian Empire was

on Germany during the war. The empire was deep in decline, its army wildly diverse ethnically in a time of rising nationalism, under-manned, under-gunned, and inexpertly commanded. Through diplomatic ineptitude, they even managed to draw in an additional enemy against the

Central Powers, Italy. In the course of the war, the Dual-Monarchy required the Kaiser's assistance in conquering its original adversary, Serbia, and—to avoid collapse several times on the Eastern Front—assistance in the Carpathians in 1915 and against the Brusilov Offensive of 1916. Only the German troop deployments at Caporetto made that attack feasible and saved the Austro-Hungarian position on the Italian Front in 1917. All of these "extra responsibilities" had, of course, the greatest impact on the German planning and operations on the Eastern Front during the Hindenburg-Ludendorff regime. Admiral Tirpitz described the situation as being "tied to a corps."

The partnership's second on going distraction was the unpredictable support from their two superiors, Kaiser Wilhelm and the new Chief of the General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn, who had succeeded Helmuth von Moltke after the First Battle of the Marne. Falkenhayn initially recommended negotiating a peace settlement with the Russians and focusing on the war against France. This approach was blocked

quickly due to a meeting of the minds of the Austrian high command and his own commanders in the East. Falkenhayn's thinking next moved to an offensive strategy on the Western Front, while conducting a limited campaign in the east. He hoped that Russia would accept a separate armistice more easily if it were not humiliated too much. This still brought him into conflict with Hindenburg-Ludendorff, who favored massive offensives in the east. In effect,

Ober Ost argued for an inversion of the Schlieffen Plan concept of knocking out France quickly to concentrate on Russia.

At Last, at the Kaiser's Side

Other initiatives in 1914 failed for Hindenburg. He felt the Russian Army simply had too many troops at that point. After the turn of the year, however, the clear stalemate on the Western Front found the Kaiser open to other possibilities. Convinced by Hindenburg-Ludendorff of the possibilities on the Eastern Front, he intervened for once in the disputes among his commanders and ordered that the major military effort for 1915 take place in the East. Falkenhayn accordingly strengthened German forces there with a new army (Tenth) and authorized the formation of a new, mixed Austrian-German force to cooperate with Habsburg efforts in Galicia. On the surface, the stupendous 1915 success in the south with the Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive and at an earlier victory in the north at the Second Battle of Masurian Lakes, were substantial victories. The partnership was credited with massive territorial gains and having inflicted hundreds of thousands of casualties on the enemy. Yet, oddly, the Russians were still in the war. Further, garrisoning larger territory required more troops and the Central Powers planners began realizing they were starting to run out of manpower. To the disappointment of Hindenburg-Ludendorff, the Kaiser and Falkenhayn were losing their enthusiasm for the East and planned to move some of the partnership's forces to the West. Fighting on both fronts in 1916 would be of a different character than in 1915. These changes, though, would also open a surprising opportunity for the partnership.

The following year brought the downfall of the hated Falkenhayn. Behind the scenes, the political infighting had been brutal. Falkenhayn had found it hard to counter the partnership's aggressive Eastern Front strategy given their national popularity. Ludendorff openly hated the Chief of Staff and found it impossible to work with him. In retaliation, Falkenhayn had tried to transfer Ludendorff out of his headquarters position and even asked Hindenburg to retire. Kaiser Wilhelm personally disliked both Ludendorff and Hindenburg's personal ambitiousness but needed to publicly support them.

Double Portrait by Hugo Vogel

Against this backdrop, Erich von Falkenhayn had an utterly disastrous 1916. His advocacy of the blood-draining Verdun Offensive committed his nation to an attritional battle at a time when Germany was running out of manpower. The Allied offensive on the Somme was strongly resisted, but it was allowed to turn into a second attritional struggle. Finally, during the summer of 1916, his long-held view that Romania with its substantial 650,000-man army would never join the Allies in the war proved incorrect. They joined the Allies when the Brusilov Offensive showed Russia was still dangerous. Kaiser Wilhelm lost all confidence in his warlord. Falkenhayn had to go. For Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg, the army and the nation, the choice was obvious. His Majesty had deep reservations about the pair, both individually and collectively, but he made the appointment of Paul von Hindenburg to the post of Chief of the Great General Staff on 29 August 1916. Ludendorff demanded joint responsibility for decision making and authority to sign most orders. Hindenburg did not refuse and authorized that a new position, First Quartermaster General of the Great General Staff, be created to emphasize Ludendorff's nearly equal and comprehensive authority. The pair had completed their march from anonymity to supreme command.

Sources: Battles East by Irving Root; The Eastern Front, 1914-1920 by Neiberg and Jordan; Wikipedia

100 Years Ago:

|

World War I for the Serious Hiker

The Walk of Peace

View from an Italian Mountaintop Artillery Position

A system of trails has recently been organized around the battlefield of the Isonzo River (now Soca River) sector of the Italian Front. One and a half million soldiers died, were wounded, taken prisoner, or went missing in the course of one Austro-Hungarian and 11 Italian offensives on the Isonzo Front (1915–17). More than 250,000 lives were lost in grim battles fought in this mountainous area that today appear so idyllic. In fact, the beautiful river valley is a major resort in both the summer and winter.

As of 2015, 400 km of hiking trails in this sector are now connected in a Walk of Peace that stretches from the Julian Alps to the Adriatic. The trails go along the both the Italian and Austro-Hungarian front lines linking their wartime remnants, including fire trenches, high observation posts, excavated galleries, natural caves, and bunkers. Along the well-marked route are also found award winning indoor and outdoor museums, memorials, and, sadly, a number of cemeteries and ossuaries. Although the trail was inspired by the memories of war, the walk is intended to be a celebration of peace as a secondary goal.

General Route (Slovenia in Dark Blue)

Another goal of the trail is to promote harmony between the neighboring nations that once fought against each other. "Since there are no living witnesses, passions and emotions have calmed down considerably. The legacy of WWI no longer separates people, but it really unites them," explained Maša Klavora, director of the Ustanova Fundacija Poti miru v Posocju, which helps manage the trail.

Path to an Austrian War Chapel Memorial

The trail network consists of 15 sections that vary in length and difficulty; it is clearly marked and mainly runs on existing mountain and tourist trails. Special attention has been given to the battlefields around Kobarid (formerly Caporetto) and the Carso Plateau to the south, which were scenes of intense fighting. A Walk of Peace guidebook has been published in Slovenian, English, Hungarian, Italian, and German and can be ordered at: turizem@potmiur.si.

Kiosks in a Cavern Occupied During the Fighting

Your editor, who has led battlefield tours to the area and walked sections of the trails, feels this is some of the most thrilling scenery he's seen anywhere, let alone on a battlefield. He does suggest, though, that you thoroughly research your excursions on the Walk of Peace. There's good reason why you see the lawyer's disclaimer "! You walk along the Walk of Peace at your own risk." Given the terrain and changes in elevation, the easiest sectors are a vigorous hike, and the most challenging require some experience with mountaineering and appropriate equipment.

Sources: BBC; TripAdvisor; Wikipedia

A World War One Music Video

Pack up your troubles in your old kit-bag

And smile, smile, smile,

While you've a lucifer to light your fag,

Smile, boys, that's the style.

What's the use of worrying?

It never was worthwhile

So pack up your troubles in your old kit-bag

And smile, smile, smile.

This song is a World War I marching song published in 1915 in London. It was written by Welsh songwriter George Henry Powell under the pseudonym of “George Asaf” and set to music by his brother Felix Powell. The popularity of the song continued into World War II. It became a staple of various music hall stars and helped to boost the morale of the British public during the war.

The pair were educated at St Asaph Cathedral, where George was a chorister, and Felix is said to have been the organist by age 12. This combination of George's lyrics and Felix's skill on a keyboard had already made them music hall favorites even before their most famous hit.

But" Pack Up Your Troubles" took them to another level of fame, with the song being translated into around a dozen languages—including German. It was a success, which the brothers told reporters at the time, they were at a loss to understand.

"A few months later a wire [telegram message] came up to us at the Grand Theatre, Birmingham - PACK UP YOUR TROUBLES FIRST PRIZE. It gave George and me the best laugh of our lives," recalled Felix in a newspaper article at the time.

"On the following Monday, we put the song into our own show at Southampton in order to "try it on the dog" so to speak. "By the middle of the week we were as amused as we were delighted to hear thousands of troops singing it en route for the docks."

But with success came heartache and bitter creative differences between the brothers. George had been a lifelong pacifist, and as a conscientious objector, he had reservations about his tune's use as a rallying cry from the outset. Felix, on the other hand, immediately signed-up, and spent the war as a staff sergeant touring the trenches with their morale-boosting ditty.

Sources: Library of Congress, BBC, YouTube

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon